Anthony McWilliams first became familiar with Primal Pictures’ Anatomy.TV during the long and arduous academic and clinical journey that culminated in his current position as a trauma and orthopedic consultant, or senior surgeon, specializing in hip and knee replacements in Great Britain.

“I used Anatomy.TV to look at the anatomy for surgical approaches — how do you get to the forearm from the front and what nerves do you need to make sure you avoid or what muscles do you need to preserve and shuffle out of the way if you’re going to fix a forearm fracture? That sort of thing,” says McWilliams, who is based at Barnsley Hospital, part of the National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, in the city of Barnsley.

But it was while working on a required research paper that eventually turned into a doctoral thesis that McWilliams gained a deeper appreciation for what Anatomy.TV could do. As McWilliams began his six years of training as a registrar — a training period for doctors similar to a resident in the U.S. — a new rule was handed down requiring orthopedic registrars to publish a peer-reviewed paper on original research before completing the program.

McWilliams worked with Martin Stone, a research-oriented orthopedic surgeon in Leeds, to study leg length inequality following total hip replacements. As McWilliams dug deeper into the research, the paper he began working on to fulfill a requirement to become a consultant evolved dramatically – first, to a master’s of engineering thesis, due to the amount of engineering involved in hip and knee replacements, and finally to a doctoral thesis for an MD(Res) degree in the UK completed in 2017.

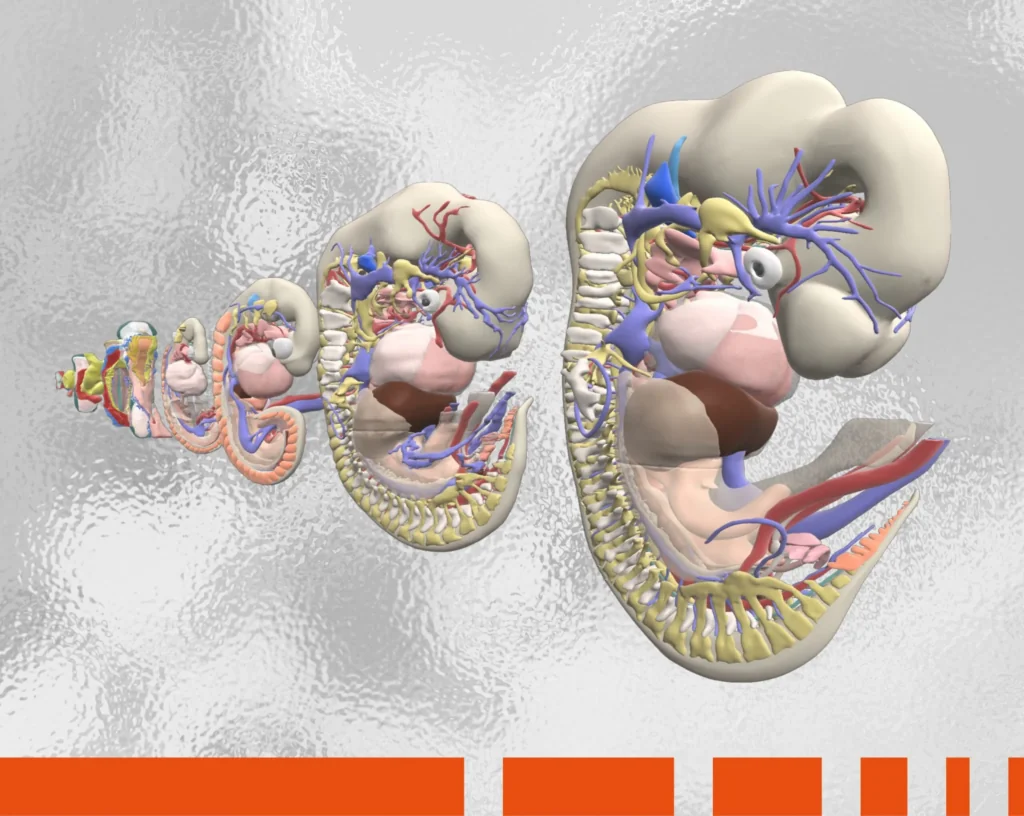

As he wrote his thesis, McWilliams recalls, “I was looking at how to describe the ways that the pelvis can tilt. Now, the bony pelvis is quite a complicated structure. Like everything, it can move in six degrees of freedom. It can move up and down, side to side, and front and back. But it can also rotate on those axes. So in the first part of my thesis, in the glossary, I needed digital images of the pelvis I could put arrows on to describe what’s pelvic tilt, what’s pelvic obliquity, what’s pelvic rotation.”

Having been impressed with the quality of images he had seen in Anatomy.TV, McWilliams asked Primal Pictures for permission to include some of the product’s digital images of the pelvis in his doctoral thesis. The request was granted, since it was for a non-commercial use.

It solved a major problem that I had in terms of getting good, quality images to describe the movements of the pelvis.

“I’m very grateful to Anatomy.TV for letting me use their images in the thesis,” McWilliams says. “It solved a major problem that I had in terms of getting good, quality images to describe the movements of the pelvis.”

In fact, he says, when he included the images following initial review, “they were complimented upon, actually.”

McWilliams, who had access to Anatomy.TV through the NHS during his years of training to become a consultant and now has access through the Royal College of Surgeons, says he continues to find the 3D product useful.

“It was the functionality of it that I found most appealing,” he says. That includes being able to click through the different layers, spin the anatomy around, get clinical images and MRI scans, and review details of topics such as the course any given nerve takes through the body.

“I’ve used Anatomy.TV throughout my training to remind myself of the anatomy to go through in a surgical approach I haven’t done for a while,” McWilliams says. “I still use it, actually. If I’m doing an operation I haven’t done for a while on a broken bone, I just have a quick flick-through on the anatomy to make sure I understand it beforehand. It’s quite reassuring.”

Like most doctors in the NHS, McWilliams does some teaching. And he has found Anatomy.TV to be a helpful tool there as well.

“I use it just to go over the anatomy,” he says. “For instance, there’s quite a complicated way of classifying fractures around the ankle called Lauge-Hansen that requires you to understand what position the foot was in and then what ligaments were tight at the time. Once you understand it, it makes an awful lot of sense. But to understand it, you have to understand the anatomy.”

More recently, McWilliams found it helpful to use Anatomy.TV to review the anatomy around the hip as he learned about a new surgical approach to the hip called the SPAIRE technique.

“As a hip surgeon, there are essentially two or three generally accepted ways to get into the hip. I routinely use the posterior approach. If you feel the bony part of your hip, there are some surgeons that go in just in front of that bony part of the hip. Some surgeons go around the back for the posterior approach, and I’m one of those. There’s a smaller group that goes in at the front. That may be emerging, but it’s still yet to generally bed in.

I've just been to some training for what's called the SPAIRE approach where you can go in through the back of the hip, but without damaging very many muscles. That approach requires a fairly detailed understanding of the anatomy, which I have. But it's useful to picture It.