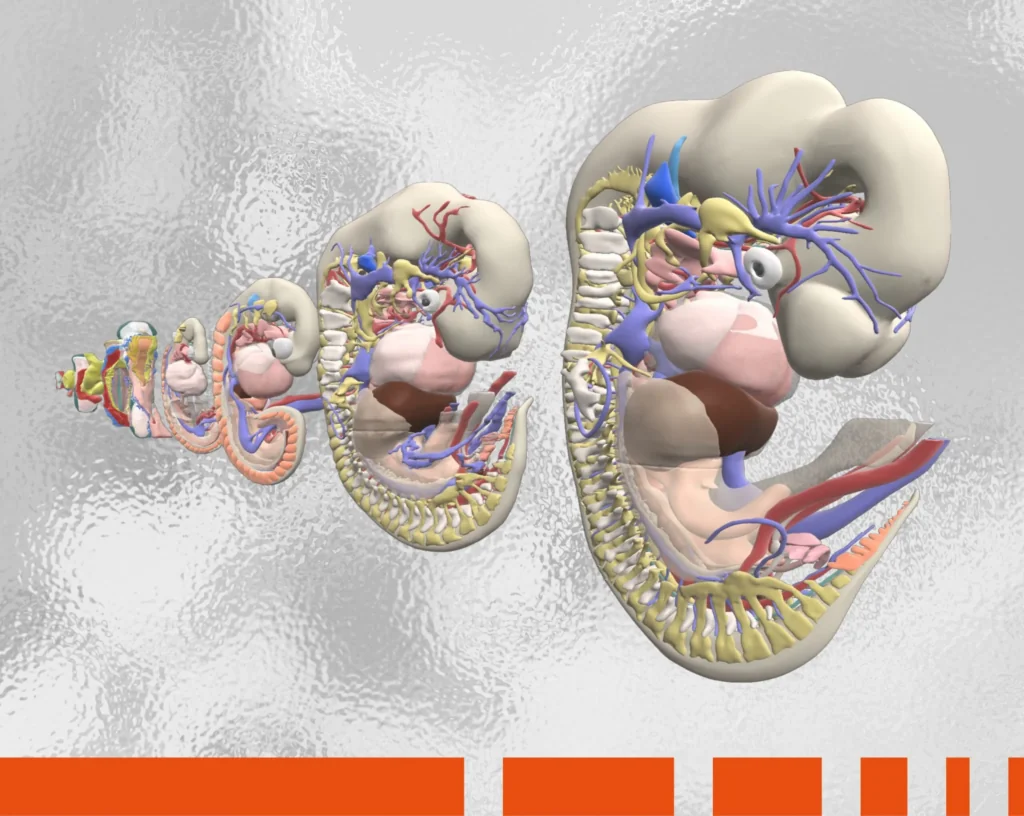

Say cheese: World Smile Day is coming up on Oct. 6! Begun in 1999 by the commercial artist who first created the now-ubiquitous “smiley face” back in 1963, World Smile Day has a simple theme: “Do an act of kindness, help one person smile.” But how, exactly, does one physically smile? The answer is more complex than it may seem on the surface, involving an intricate set of muscle and tendon movements working in conjunction with their blood and nerve supplies.

The Anatomy of a Smile

You’ve heard the old adage, “it takes more muscles to frown than it does to smile”? While the average human face has 43 muscles (although there may be variations among individuals), coming up with the conclusive number used while smiling has proven tricky, since the definition of a smile can range from the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smirk to Jack Nicholson’s crazed grin in Stanley Kubrick’s classic horror film The Shining.

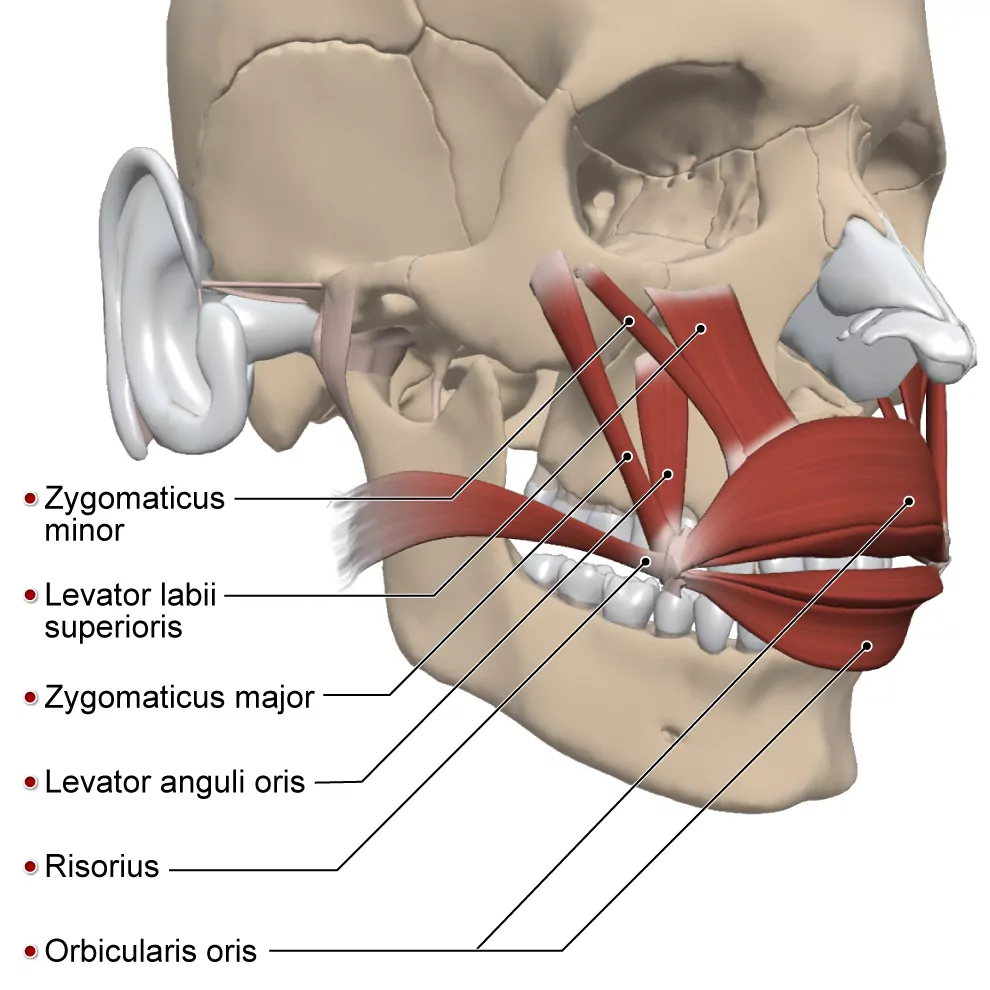

Research has shown, however, that these six main muscle pairs (12 “smiling muscles” in total) spring into action when you flash a grin:

-

- Levator anguli oris – raises the mouth’s angle

- Levator labii superioris – elevates the mouth and upper lip

- Orbicularis oris – responsible for opening and closing the lips

- Risorius – pulls the sides of the mouth outward

- Zygomaticus major and zygomaticus minor – sometimes called the “smile muscles” or “laughing muscles” as they pull the corner of mouth upward and outward.

In case you’re wondering, researchers haven’t reached a consensus on the exact number of muscles needed to frown, either, but generally agree that it’s fewer than the number needed to grin.

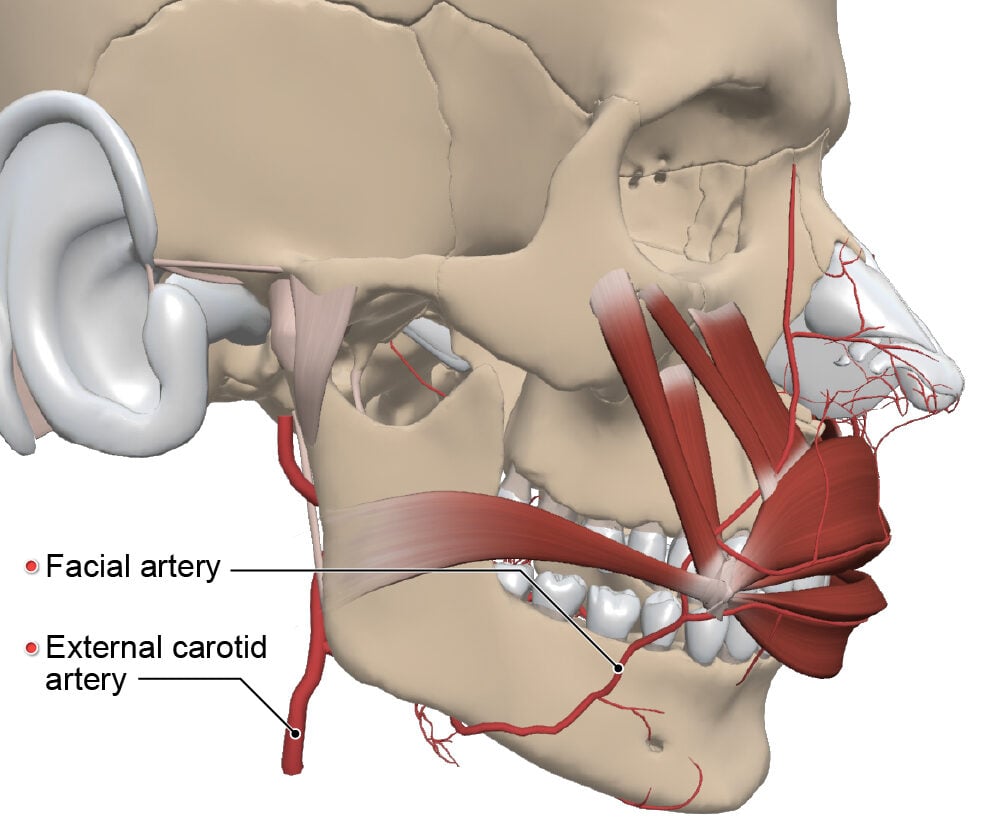

Arterial supply and venous drainage

Continuous supply of oxygen and nutrient rich blood is essential for the smiling muscles to work. This job is carried out by different branches of facial artery, which originate from the external carotid artery.

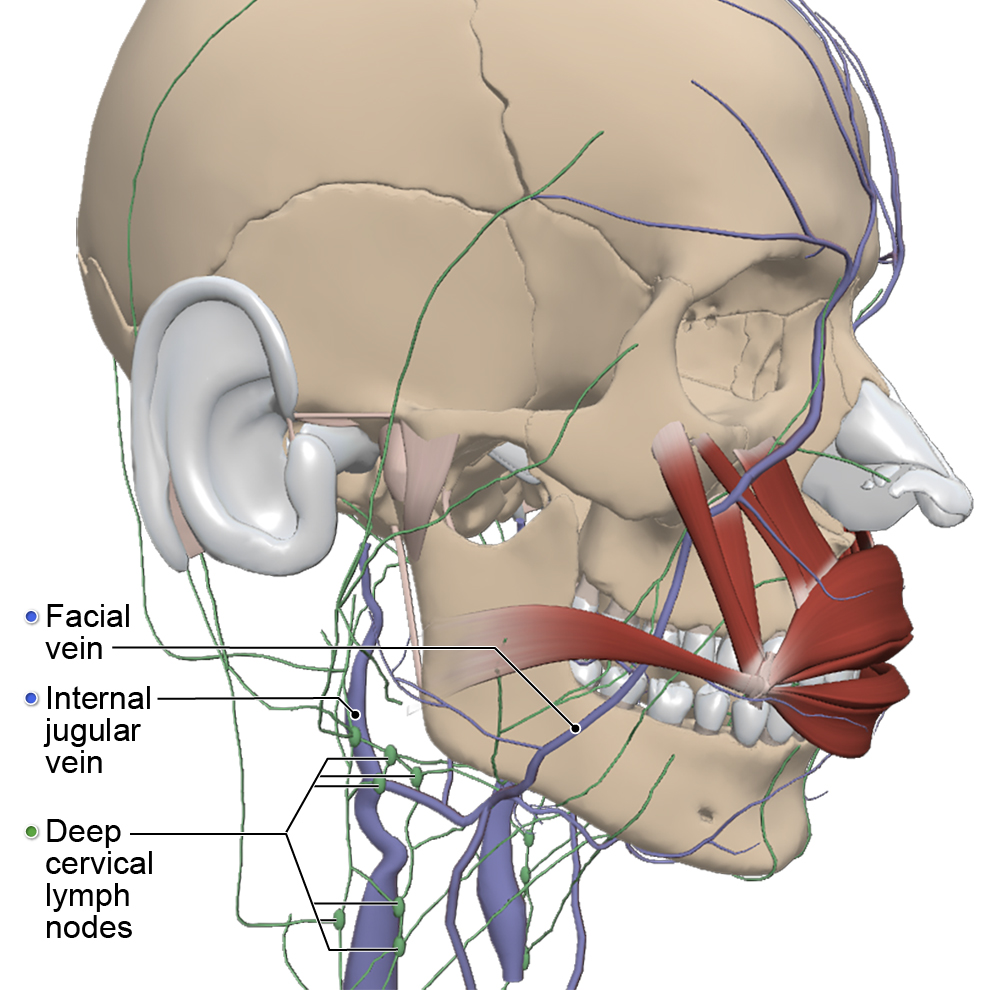

While the facial artery supplies fresh blood to the smiling muscles, different branches of the facial vein collect oxygen and nutrient-deprived blood back from them, which get drained into the internal jugular vein to be sent back to the heart and lungs. There, the blood gets filtered and re-loaded with fresh oxygen and nutrients, ready for another round. This circulation of blood is hard at work behind the scenes, ensuring your ability to keep flashing those pearly whites.

Nerve innervation

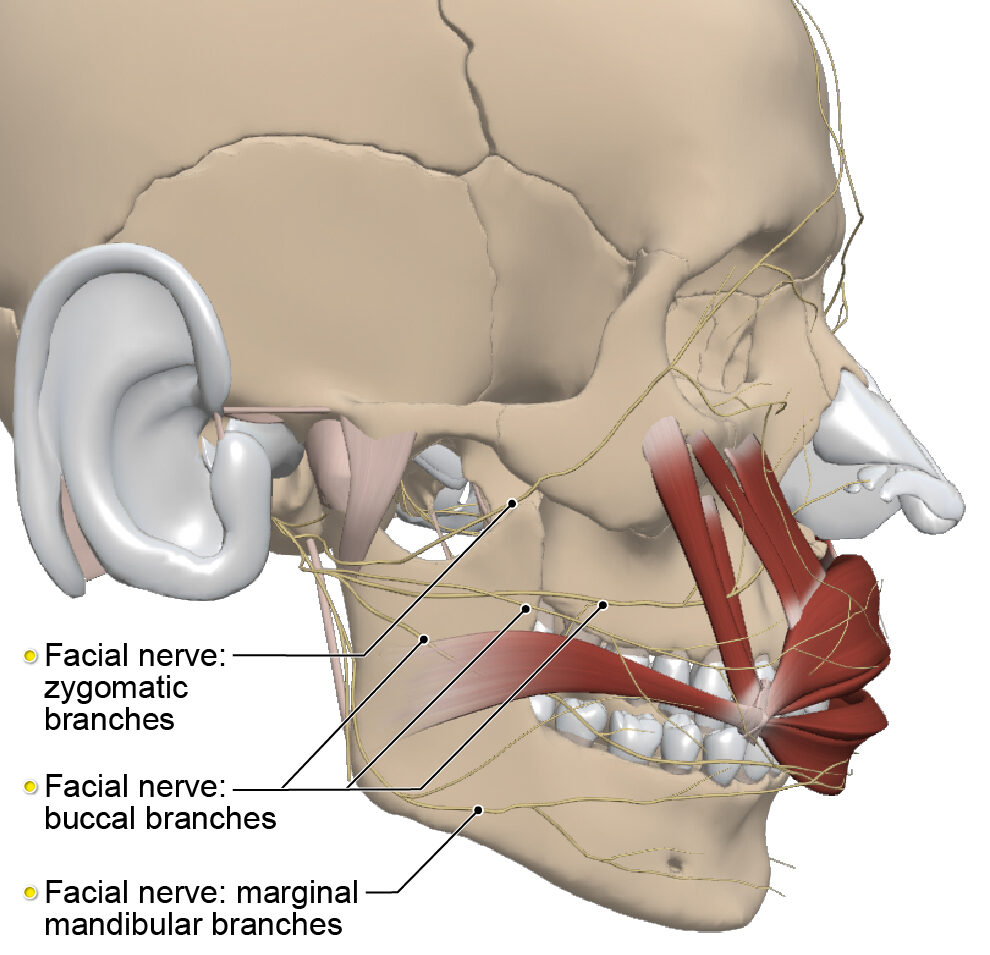

Before your muscles contract to create a beautiful smile, they first need to receive signals from the brain to do so. Different branches of the facial nerve are responsible for receiving these signals and innervating the smiling muscles:

-

- Buccal and zygomatic branches innervate the levator anguli oris, levator labii superioris, risorius and zygomaticus major and minor.

- Buccal and marginal mandibular branches innervate the orbicularis oris.

When smiling isn’t easy

Sometimes the signals from these nerves to the face don’t transmit as planned. While many of us take the act of smiling for granted, there are a number of clinical conditions – many related to the nervous system – that can impact one’s ability to form this universal expression. The interruption of signals from the brain to the facial muscles, such as nerve injury, can cause paralysis or weakness in the face, sagging of facial features or drooling and inhibit or prevent the ability to form a smile. Symptoms may be localized to one area of the face, impact certain quadrants of the face or affect the entire facial area. Causes for this brain signal interruption are varied, ranging from auto-immune diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS), to head and neck tumors, to bacterial infections such as Lyme disease, to accidents or injuries and stroke.

If you or someone you know experience facial weakness or palsy and the inability to form a smile, seek medical attention right away, as it may indicate a temporary problem or serious condition.

Can the act of smiling change your mood?

Now that we’ve explored the anatomy of a smile, what about its emotional aspects? Picture it: You’ve had a tough day at work, traffic was terrible and when you return home, you realize you left your refrigerator door open and everything inside has spoiled. You feel like screaming, or maybe even crying. But what if you… smiled? Some research suggests that the act of exercising your zygomaticus major muscle and orbicularis oculi muscle – the same as those used when we smile – can actually make us feel better. According to research, even if your heart is not in it, activating these facial muscles has been shown to stimulate endorphins , a type of hormones blocking feelings of pain and increasing feelings of wellbeing. In the same way experiencing a positive emotion can trigger a smile (creating a “happiness loop”), the act of smiling can stimulate the body’s production of these “feel-good” endorphins.

Additional research has found that facial feedback to the brain – including the act of smiling – influences emotional experience in a small but significant way. So the next time you’re waiting at a crowded restaurant for a friend who is late (again) and someone is chewing loudly at the table next to you while having a loud argument on their cell phone – instead of screaming, try putting on a smile!

Bonus fun facts about smiles

-

- Smiling relieves stress: A 2012 study from the University of Kansas found there is truth to the phrase “grin and bear it,” and that the act of smiling actually lowers blood pressure.

- There are 19 different types of smiles, meaning not all smiles are created equal! Researchers have catalogued a wide variety of smiles, conveying everything from fear, to contempt – to embarrassment. These include the Duchenne smile, produced when feeling genuine happiness and consisting of the contraction of both the zygomatic major (lifting the corners of the mouth) and the orbicularis oculi (engaging the muscles around the eyes and pulling up the cheeks), resulting in what Tyra Banks coined the “smize,” or smiling-with-the-eyes effect.

- Smiling is contagious: The notion that you can spread good cheer by smiling is a scientific fact, according to research. Scientists examined the tendency to simulate the facial expressions of others in social situations, which suggests that the impulse to mimic others’ facial expressions can trigger the same emotional state in ourselves.

The images in this post are from from Primal’s 3D Real-time tool. To learn more about this or other Primal learning resources, please fill in the form here and our team will be in touch.