When it comes to their anatomy, do two hearts really beat as one? This Valentine’s Day, we explore the implications of the anatomical differences of the heart that exist along sex lines, and why we should incorporate these factors into healthcare decisions more often.

Note: Please see more info below about our use of language when describing female and male characteristics.

Take heart this Valentine’s Day

Does the thought of receiving a big box of chocolates for Valentine’s Day make your heart skip a beat? Or is your heart just not in it this year? No matter how you commemorate (or ignore) the holiday, there’s no denying that the heart plays a central role in the traditions and iconography of Valentine’s Day. But the heart shape we’re used to seeing on Valentine’s cards or in emojis is a far cry from the appearance of the actual human heart, which is roughly the shape of a cone, about the size of a fist, and the hardest working muscle in the human body.

However, not all hearts beat the same. Subtle anatomical and physiological differences are common, and characteristic variations can be observed between the hearts of females and males. These differences are likely a major influencing factor behind the sex gap in cardiovascular diagnosis and treatment; cardiovascular diseases remain under-treated and under-diagnosed in females. To understand these variations and their clinical relevance, we must first discuss the general anatomy of the heart.

The content in this post is from Primal’s Human Anatomy & Physiology (Cardiovascular System module). To learn more about this or other Primal learning resources, please fill in the form here and our team will be in touch.

How does the heart fit into the cardiovascular system?

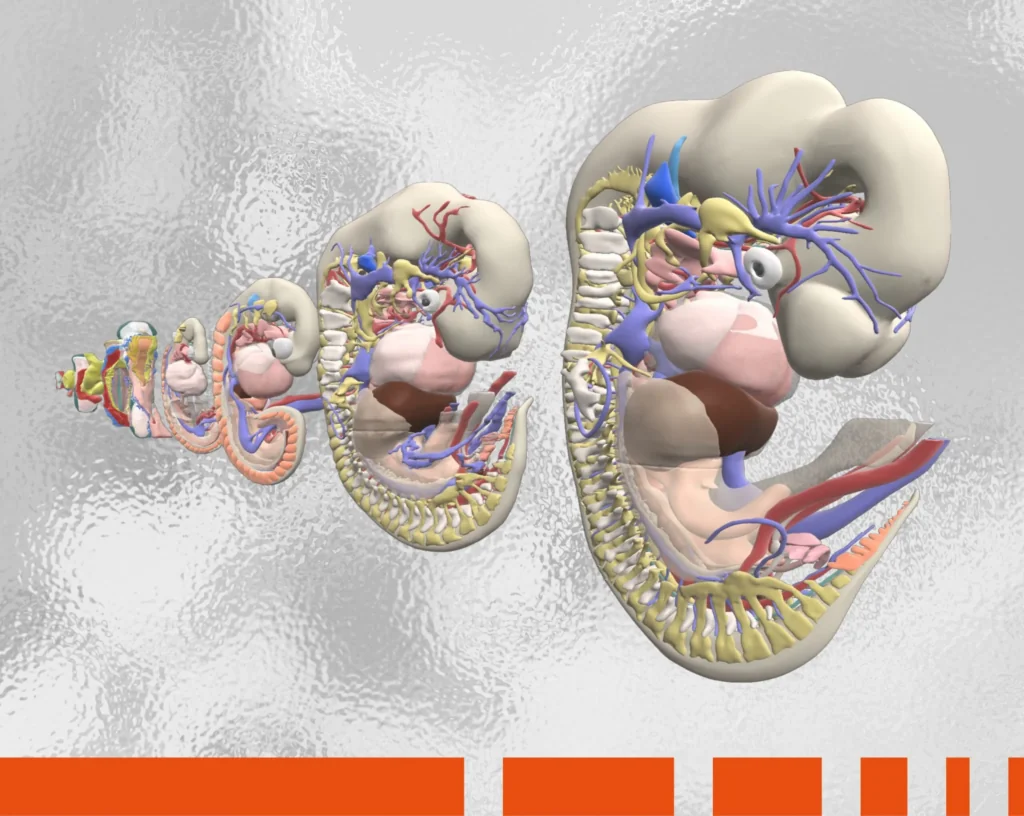

The heart is the main organ of the body’s cardiovascular system, responsible for pumping roughly 7,600 liters of blood per day through the body’s blood vessels. This circulation supplies millions of cells with necessary oxygen and nutrients while also removing unneeded waste products like nitrogen and carbon dioxide.

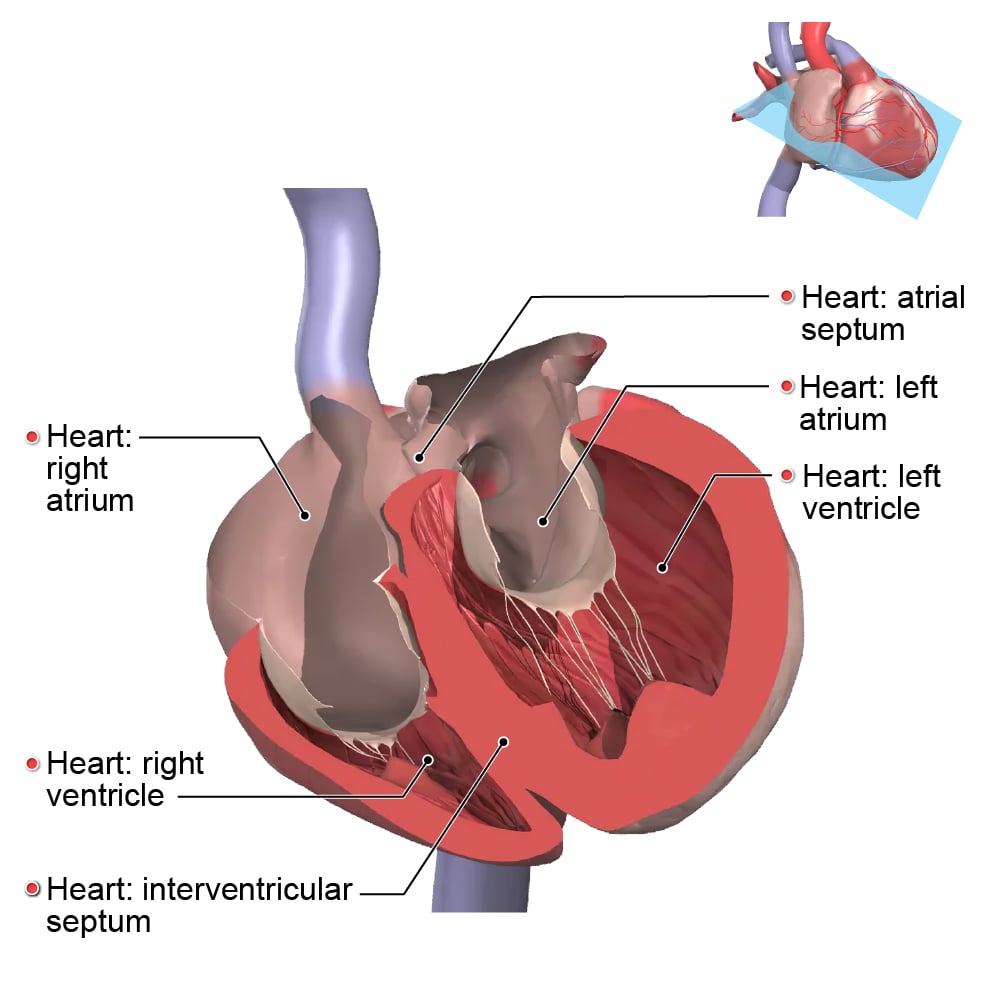

The heart consists of the upper and lower chambers. The upper chambers of the heart are the left and right atrium, which are divided by the atrial septum. The atria are responsible for receiving blood returning to the heart from the lungs and the rest of the body. The lower chambers of the heart are the left and right ventricles, which are divided by the interventricular septum. The ventricles have thicker muscle walls than the atria and make up most of the mass of the heart. The blood gets pumped out from the ventricles when their thick muscle walls contract before being delivered to the lungs and the rest of the body.

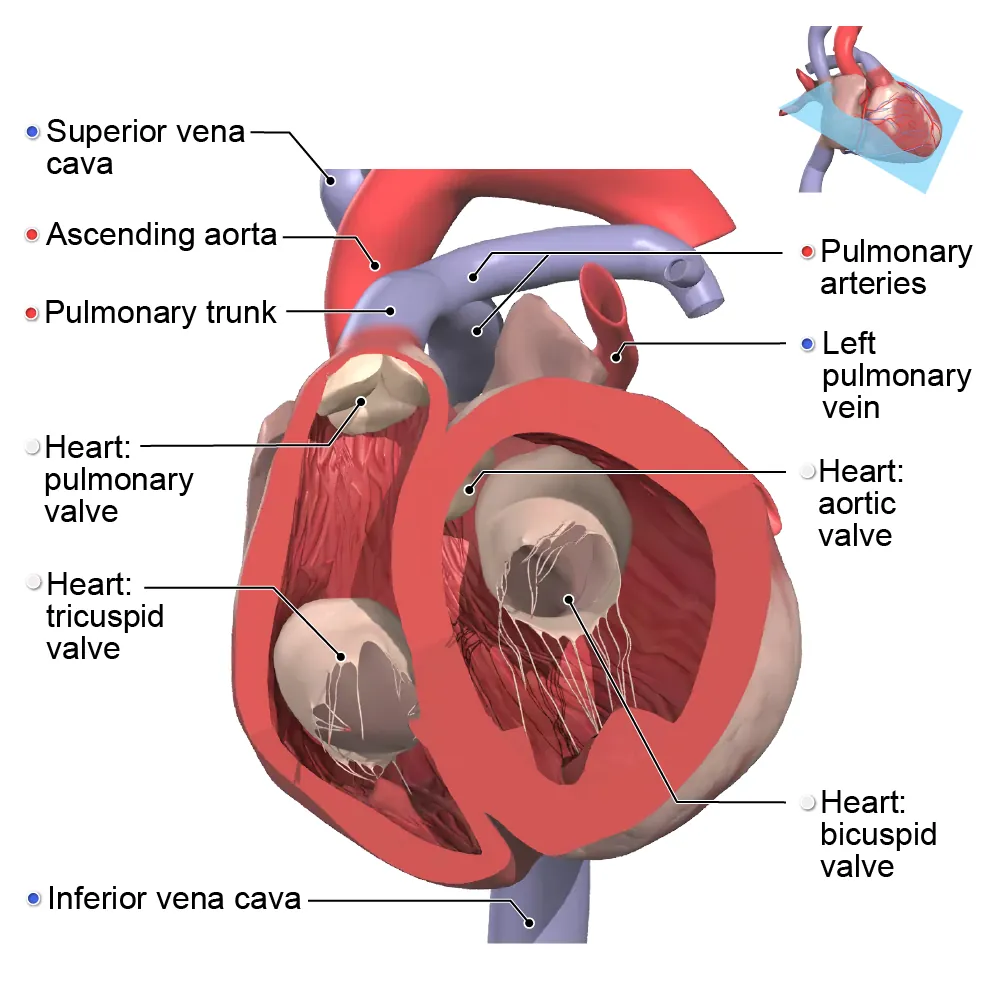

The blood leaves the heart via the aorta and pulmonary trunk and returns to the heart via the superior and inferior venae cavae and pulmonary veins. Together, these arteries and veins are referred to as the great vessels of the heart.

Each great vessel of the heart has a valve that works as a gatekeeper for the organ — ensuring blood flows only in certain directions, preventing it from flowing back in the direction it came from. There are four valves in total that align vertically behind the sternum, starting at the top with the aortic valve, followed by the pulmonary valve, bicuspid valve, and finally the tricuspid valve at the bottom.

What are the differences between female and male hearts?

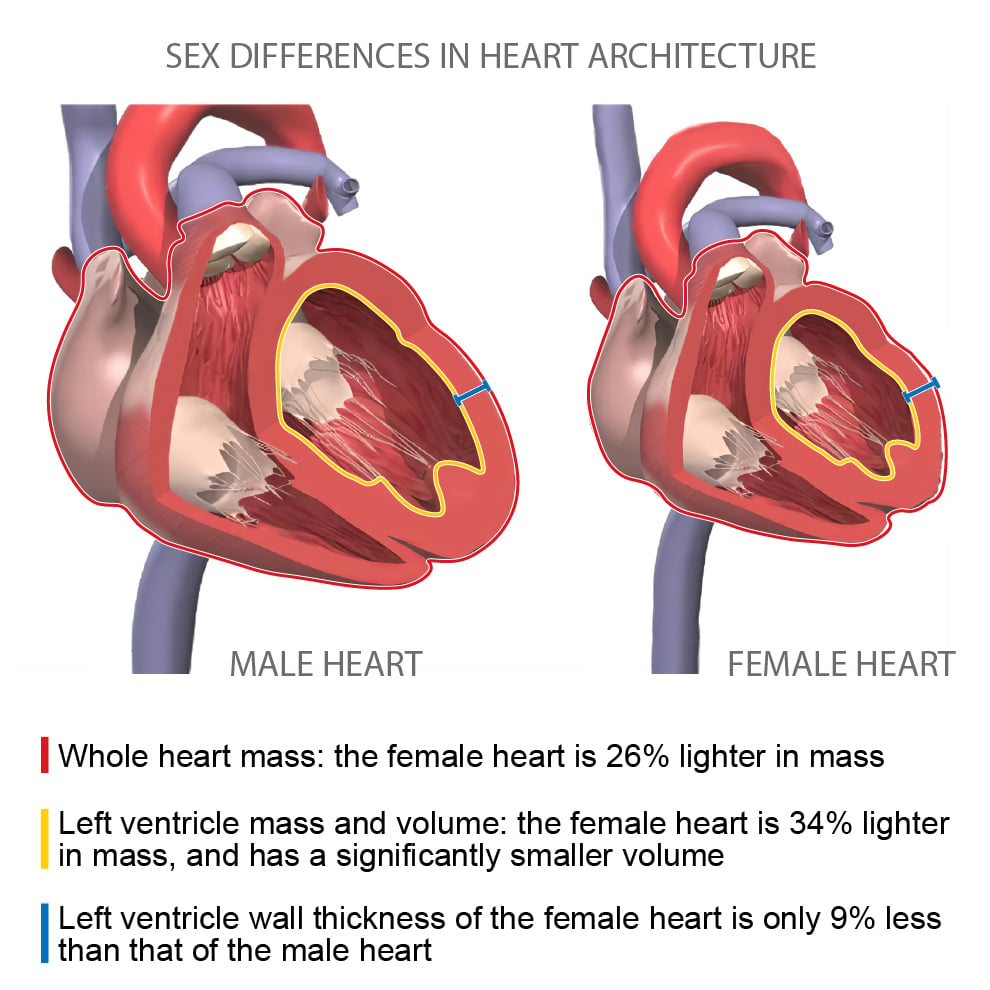

While the basic anatomy and function of the human heart is the same, there can be significant variation between the hearts of males and females — differences that can have important implications for cardiovascular health.

One such key difference is the size of the heart. At birth, female hearts tend to be slightly larger than those of males. As humans age, the cell mass of the heart stays the same, but the volume of those cells increases. During puberty, the male heart grows faster and larger than the female heart in volume, resulting in a notable size difference between the two by the time adulthood is reached. Adult female hearts are roughly one quarter smaller than those of males.

But it’s not the case of a simple proportional scale-down: Scaling down does not reflect the geometric differences between male and female hearts. In addition to the more obvious size difference, variations of the heart in structural, microstructural, and functional levels are present as well. These structural and functional differences are the result of diverse contributing factors, including genetic variation, tissue and cell response to sex hormones, and body size. Importantly, these variabilities can lead to females being under- and un-diagnosed for cardiac disease, since diagnostic criteria is historically built on studies of the male cardiovascular system and its typical characteristics.

For example, cardiac enlargement is a common risk factor for sudden cardiac death, but the definition of what constitutes an enlarged heart is based on studies of adult male hearts, which, as we learned, are inherently larger than adult female hearts. Similarly, if studies conducted on male hearts were scaled for females by lean body mass (the mass of the body without adipose tissues), they would not accurately reflect the actual cardiac differences between the sexes. While the mass of the left ventricle roughly reflects the difference in lean body mass between the sexes, it overscores the differences in right ventricle mass and overall heart mass. These differences show that scaling by lean body mass alone is not sufficient for eliminating sex differences in cardiac geometry.

Another study that used cine magnetic resonance imaging to study sex-specific differences in cardiac function supported the notion that sex-matched values should be considered when evaluating cardiovascular health.

These variations of the structure and microstructure of the heart, plus different physiological responses to circulating hormones, contribute to overall differences in cardiovascular parameters, such as:

-

- Stroke volume and ejection fraction: Due to the differences in the volume of the left ventricle, the stroke volume (total volume of blood pumped out of the left ventricle during a heart contraction) of the female heart is generally smaller than that of the male heart. The ejection fraction is the percentage of the total blood volume pumped out with each heartbeat as compared to the stroke volume and is an indicator of ventricular efficiency. Interestingly, even with a smaller ventricle, the ejection fraction is slightly higher in females than in males.

-

- Heart rate: The heart rate of females is faster than that of males. Female hearts have a smaller left ventricle volume but can pump out the same amount of blood in the same amount of time as their male counterparts.

-

- Cardiac output: Cardiac output is the product of heart rate and stroke volume measured in liters per minute. The higher heart rate of females makes up for some of the differences in systolic volume. However, the cardiac output of females remains generally smaller than that of males.

-

- Contractility: The female heart has greater contractility, the ability of the cardiac muscle to contract and thereby pump blood.

Keeping good health close to your heart

Understanding the fundamental microstructural differences in male and female hearts is critical in bridging the gaps in cardiovascular healthcare. Despite the identification of these sex-related cardiovascular disease risk factors, heart diseases among females — especially young females — remain under-diagnosed and under-treated. Applying the knowledge of structural and functional differences of the heart among the sexes will be a critical factor in improving the accuracy of diagnoses and effectively managing cardiovascular disease. Considering these factors in clinical environments and resisting the attitude that cardiovascular disease predominantly affects males will lead to longer and healthier lives for all.

Some of the language in this article refers to sex as binary (female/male). When describing female and male characteristics, we refer to the assigned sex at birth. Assigned sex is the label given at birth by medical professionals based on an individual’s chromosomes, hormone levels, sex organs, and/or expected secondary sex characteristics.

This article discusses anatomical and physiological variation in secondary sex characteristics — physical characteristics that are related to or derived from sex, but not directly part of the genital system.

We acknowledge that sex is not a binary concept, and it may best be viewed as a spectrum comprised of many traits. Complex biological variations can occur in everyone, and the assigned sex of an individual may not necessarily correlate with the described phenotypes and characteristics.

We also recognize that Valentine’s Day is a celebration of love and can be celebrated by everyone, no matter who they are and who they love.

The content in this post is from Primal’s Human Anatomy & Physiology (Cardiovascular System module). To learn more about this or other Primal learning resources, please fill in the form here and our team will be in touch.