Smile! If you’re among an estimated 20-30% of the population, doing so will reveal an indent or indents in the skin next to your mouth, commonly known as dimples. Stemming from the Old High German word tümpel, meaning “pond,” and the Old English dyppan meaning “to dip,” the word “dimple” entered the English lexicon circa the 15th century. Dimples vary in size and depth and occur across all sexes. These beguiling divots have adorned well-known smiling faces from Shirley Temple to Harry Styles. But how exactly are these “cheek ponds” formed? Let’s dive in to discover more about dimples!

What causes dimples?

Among those whose dimples are naturally occurring (and in geographic areas where data was collected), dimples are most prevalent among the American subgroup (34%), followed by the Asian subgroup (27%) and the European subgroup (12%).

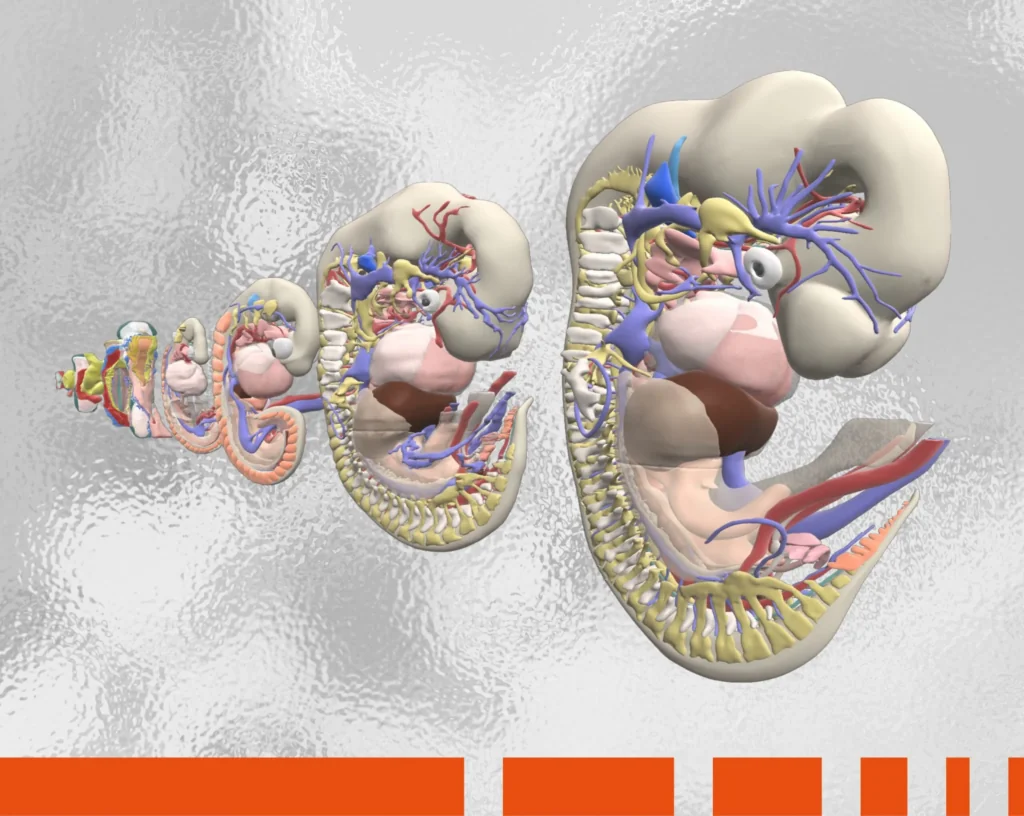

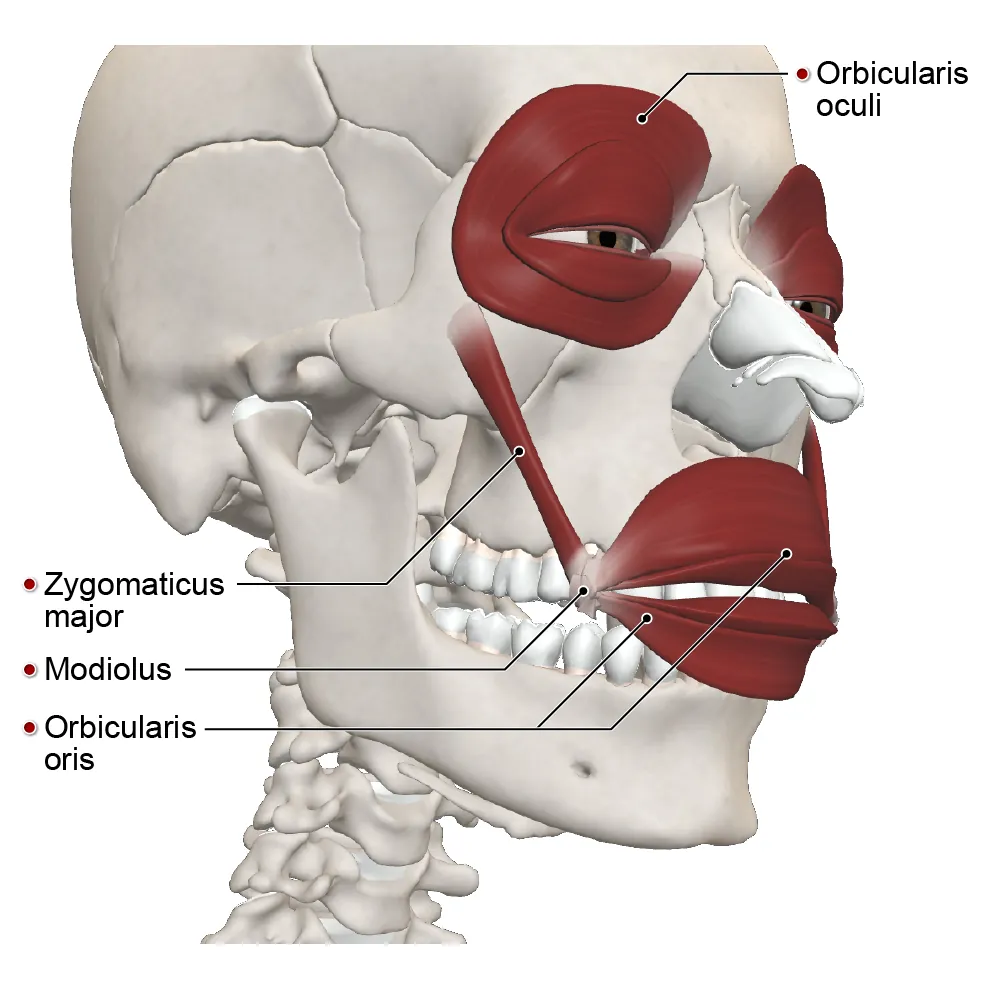

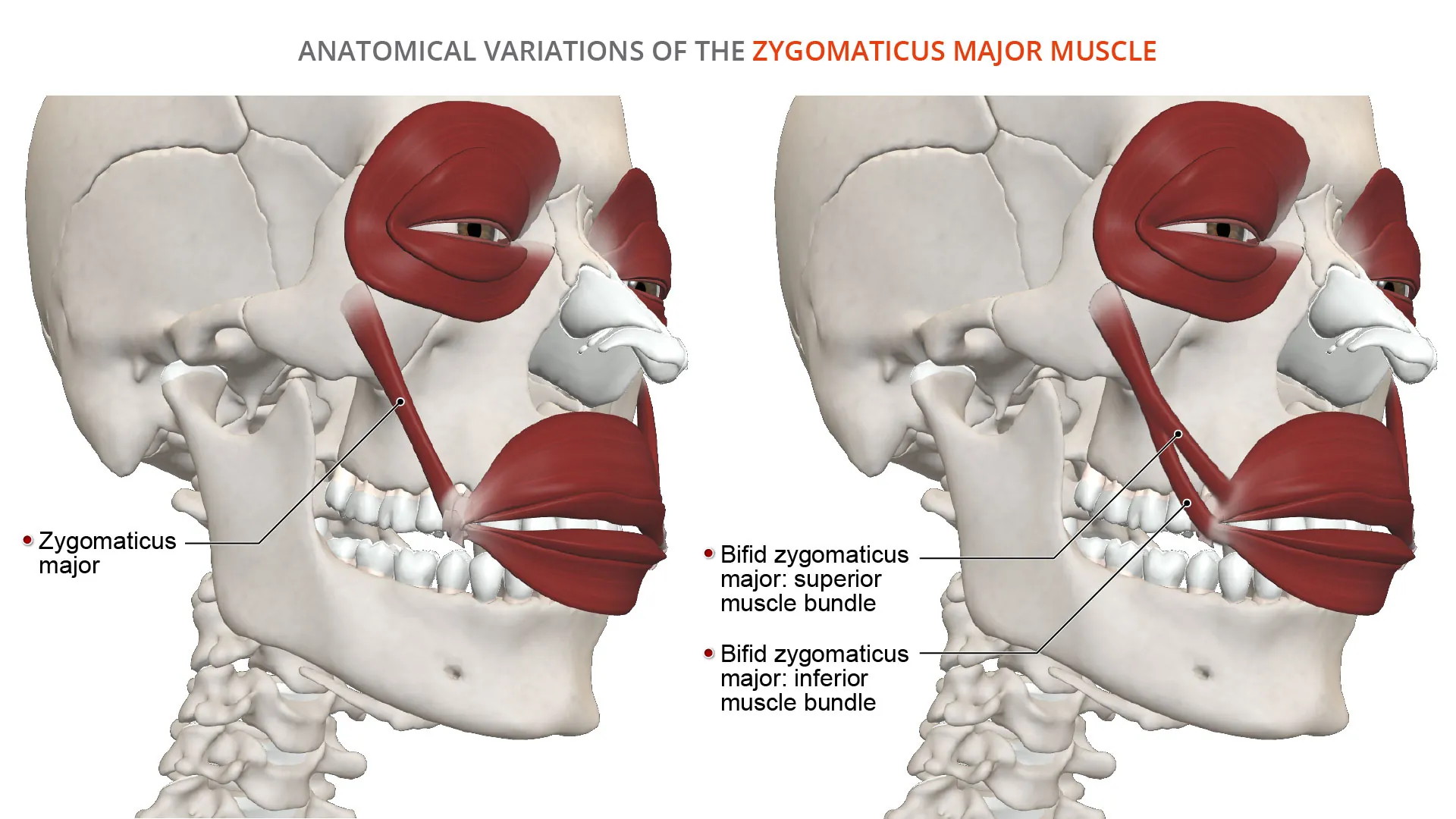

To understand what causes dimples in some people, we must look to the musculature of the face, namely, the bifid zygomaticus major muscle, a variation of the zygomaticus major muscle. The long, thin zygomaticus major muscle of the cheek originates from the lateral surface of the zygomatic bone, just in front of the zygomaticotemporal suture. It then passes down obliquely to insert into the fibromuscular mass called modiolus located at the corners of the mouth on each side of the face, and eventually merges into the orbicularis oris muscle. It is responsible for the formation of some facial expressions, pulling the corners of the mouth both upwards and outwards.

In a majority of the population, the zygomaticus major is a single band. But in those with cheek dimples, this band is actually divided into two parts — superior and inferior muscle bundles — starting at the sub-zygomatic hollow. In this bifid zygomaticus major muscle, the superior muscle bundle attaches above the corner of the mouth as usual, but the inferior muscle bundle inserts into the modiolus below the corner of the mouth. Along its midpoint, the inferior bundle also attaches to the dermis layer of the skin. This dermocutaneous insertion of these inferior muscle fibers to the dermis and the skin above the dermis causes a tethering effect, pulling the skin on the cheeks and forming cutaneous depressions — or dimples — when the individual smiles.

At least one other study suggests that lateral muscular bands around the orbicularis oculi muscle (OOc) region also play an important role in the formation of dimples.

Dimples may appear on one cheek (unilateral) or both cheeks (bilateral): one study found unilateral cheek dimples to be far more widespread among study participants. However, cheeks are not the only areas of the face where dimples can appear. While cheek dimples may be the most prevalent, dimples around the angles of the mouth are also common. These can be found opposite the angle of the mouth (para-angle), below the angle of the mouth (lower para-angle), or above the angle of the mouth (upper para-angle). Of these dimples around the mouth, the lower para-angle type is the most common.

Incidentally, while indents in the chin are often referred to as “chin dimples,” these indentations are actually the result of an unfused jawbone — which creates a gap or cleft in the chin — rather than a true dimpling of the skin

Where else are dimples found on the body?

The face is often the spot where dimples are most noticeable, but the presence of dimples is not limited to only the facial region. Although rare, incidents of bilateral acromial shoulder dimples have been reported, believed to appear either as a result of genetic abnormalities or syndromes — or as a result of fetal exposure to harmful substances. Also rare, but more widely seen, are dimples in the lower back. A sacral dimple, present in 3-8% of newborns, is a singular dimple that presents above the gluteal cleft.

Yet another dimple type on the body are the fossae lumbales laterals, or “Dimples of Venus,” bilateral dimples that appear on the lower back at the spinopelvic junction. These indents are formed by a short ligament that stretches from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) to the skin, creating an indent on either side of the spine. Considered a mark of beauty by many, it should come as no surprise that these symmetrical dimples are named for the Roman goddess of beauty.

Can you create dimples?

Speaking of beauty standards, dimples have long been associated with not only attractiveness but also good luck and good health. In fact, these little indents are so coveted by some that they are willing to go under the knife to obtain them.

The creation of dimples by means of plastic surgery is called “dimpleplasty,” a relatively simple procedure usually performed on an outpatient basis. Using the classic dimpleplasty method, a plastic surgeon makes an incision in the buccal mucosa and uses a suture to create a stitch through the skin of the cheek and the dermis, creating adhesion between the buccinator muscle and the dermis via scar tissue. The tighter the thread is pulled and knotted, the deeper these cosmetically-engineered dimples become.

One study found that, of those who underwent dimpleplasty, 32% opted for bilateral dimples on the cheeks. Of those who opted for a single cheek dimple, the left cheek was a more popular location than the right. Dimpleplasty for other areas of the body (such as the corners of the mouth) was also recorded, but was a far less popular option than dimpleplasty on the cheeks.

Are dimples hereditary?

This begs the question: Are dimples hereditary? Again, the answer is not straightforward, as research in this area is scant. Since the presence of dimples can run in families, it is usually assumed that dimples are autosomal dominant genetic traits, passed from parent to child via numbered chromosomes, versus via sex chromosomes. In the case of cheek dimples, it is chromosome 16. However, some geneticists believe that this theory is not quite correct and that dimples are instead an irregular dominant trait, meaning that their presence is most likely due to one particular gene on chromosome 16, while being influenced by other genes as well.

The content in this post is from Primal’s 3D Real-time Functional Anatomy module. To learn more about this or other Primal learning resources, please fill in the form here and our team will be in touch.